Tales from the finds

The MŪSA offers you a selection of the collection’s most significant exhibits, with plenty of stories to tell.

Dedicated to all those who wish to discover the museum with an alternative view.

You will be accompanied, step by step, along a path of total immersion into the history of Alghero and its territory. From Ancient Neolithic to Post Middle Ages. A "taster" in line with the Museum’s identity and its most characteristic features.

Now let’s start...enjoy your visit!

The sea

NURAGIC VILLAGE OF SANT’IMBENIA

This reproduction with its original artefacts gives us an insight into the society and economy of a Nuragic village dating back to the early Iron Age.

The so-called Capanna dei Ripostigli, "Hut of the hoards", undoubtedly one of the most significant constructions in the village, is a planning aspect that highlights the presence of common spaces, part of which were given over to artisan production.

The creation of a main collective open space with a clear public function, leads us to imagine the likely scenario of life and society in the village: here ‘international’ and, perhaps above all, local activities of exchange and trade were managed.

The so-called "amphorae of Sant’Imbenia" inspired by Phoenicians, but produced in Sardinia, represent the wide-ranging commercial relationships of this strategic maritime port with different areas of the Mediterranean Sea and particularly with the Phoenicians.

This important fact leads us to consider Sant’Imbenia as the oldest site on the island which was attended by the Phoenicians.

Merchants were certainly attracted by the remarkable richness of the area and its produce: oil, wine, pigs, sheep, cattle, metals such as silver and lead at Argentiera, iron at Canaglia and copper at Calabona. Hence, the presence of a considerable amount of copper ingots and metal tools.

THE ROMAN WRECK AT MARIPOSA

In the 1st century AD, a Roman ship was hit by an unexpected coastal storm and sank off the coast of Alghero, roughly at the location of what is now the campsite Mariposa.

This is the scenario we can imagine, by observing both the reconstruction of the seabed and the remains of the wreck which are housed into the museum.

Thanks to the significance of its finds, it is thought to be one of the most important shipwrecks within the Mediterranean Sea.

Among the artefacts, a large number of thin-walled ceramic-faired cups have been retrieved.

These small bowls tell us a lot about the means of transport in those times as well as about the evolution of trade in the Mediterranean basin.

Due to their typical variable diameter, the bowls were stored by piling four together, which is how the cargo was found during excavations that began in 1997.

This thin-walled ceramic production, also known as ‘eggshell-like’, for its off-white colour, is attested from the 2nd century BC to the 2nd century AD.

Trade in this product was probably deemed a modest alternative to the fine glass furnishings intended for the Roman aristocratic public.

The importance of this find is reinforced by the fact that for the first time these bowls were documented in a naval context, as part of a combined cargo of other types of trade.

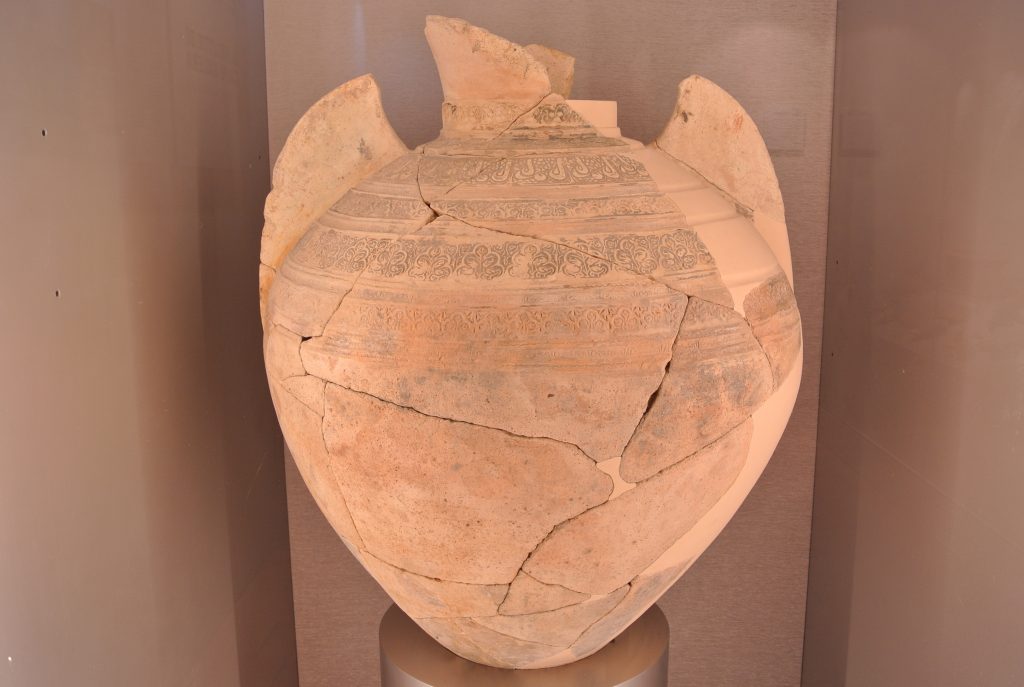

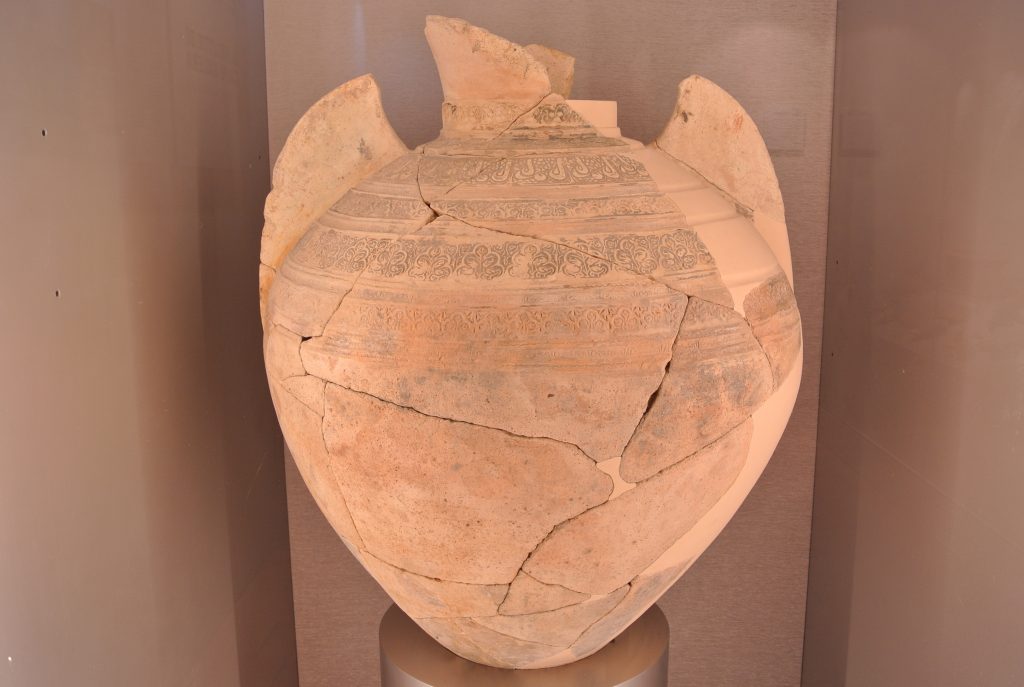

MEDIEVAL WRECK OF CAPO GALERA

This large, elegant earthen jar comes from the sea and it is believed to have been made in Andalusia between the end of the 12th and the first half of the 13th century, a period in which southern Spain was under the domination of the Muslim Almohade empire.

The jar was part of a cargo that sank off the inlet of Capo Galera, near the coast of Alghero, in a spot where the boat had stopped off along its route. Its intended destination is unknown.

The wreck was discovered in 1995 and it still lies a little more than five metres deep, on the seabed which is rich in Poseidonia thus preserving the rest of the boat and its shipload. In Sardinia and in Italy is very rare to find such a jar.

It consists of a globular container with saber-shaped handles and decorative motifs etched within horizontal bands of various sizes, placed around the upper half of it surface.

The bands are made up of leaf-shaped decorations and inscriptions of cursive and floral Culfic (a particular Arabic calligraphic style). The printed writings are repeated and appear to form some propitiatory sentences of good omen which extol Allah.

The archaeological artefacts uncovered bear testament to a vibrant life on board, mainly attributable to a crew of Arab Culture: kitchen pottery for individual and collective use, among which there is a probable couscousserie, remains of shoes, ribbed amphorae, a parchment roll holder, some wide decorated jars.

The example exhibited in the museum must have contained drinking water, a precious asset especially during the long sea crossings.

POST-MEDIEVAL WRECK OF MARIPOSA, SHIP A

Since ancient times, from East to West, the eye has been considered a symbol that wards off evil and brings good fortune. For this reason, in the wooden table of the hull, it was frequent to see carved eye-shaped decorations intended to protect the sailors from dangers and from threat during the sea crossings.

The wreck, discovered between 1988 and 1989 along the coastline, on sandy flats in front of the campsite Mariposa, respects this ancient tradition.

Following an initial investigation it appeared to be a modern vessel, albeit with features attributable to an archaic hull. However, the Carbon 14 analyses performed on the wreck revealed in fact the remains of a ship that had been built more than 100 years before it sank.

The old age of structure’s explains the presence of an eye-shaped decoration found on the left side of the prow, engraved in bas-relief on the wood.

After the naval archaeology excavation campaigns, the structure of a carrack, better known as a caravel emerged - this was an imposing sailing boat of Spanish origin, the same kind of boat that in 1492 led Christopher Columbus towards America.

Carracks were used all over the Mediterranean Sea area as merchant ships, over an extended period of time from the end of 1400 until about 1600.

This wreck is fascinating not only for its constructive characteristics, but also for its excellent state of conservation. Layers of sand, gravel and a rich seaweed mat preserved it from deterioration due to the passing of time.

The objects found inside reveal the daily habits of life on board and enable us to date the shipwreck between the end of the 15th and the beginning of the 16th century.

Wooden kegs containing salted pilchards, cooking pot, a wooden rosary, personal hygiene accessories: the archaeological artefacts narrate the sailors’ everyday life and help to reconstruct the trade routes that included Alghero and its coasts.

The lands of the living

GROTTA VERDE

The working techniques of ceramic used by the area’s ancient inhabitants are varied and fascinating.

Since the Ancient Neolithic, the production of earthenware objects is to be considered an important innovation in material culture: the first testimonies to the invention of pottery are attributable to populations from the Near East, from where this new technology then spread to the rest of the archaic world.

In the Mediterranean, in particular, the culture of cardium pottery spread. It consisted in imprinting the ridged edge of a cardium shell in the still fresh mixture of clay and water. cardium nell’impasto ancora fresco di argilla e acqua.

Examples of this type of potter include the fragments of vases found within the Grotta Verde (Green Cave), an important archaeological site at the western end of Porto Conte Bay on the promontory of Capo Caccia.

They date back to the Middle Neolithic (4,000 – 3,400 B.C.) and, specifically, to the culture in Sardinia known as “from Bonu Ighinu” : an area in the province of Sassari in which finds linked to the second phase of Neolithic in the island were first discovered.

The most elegant and refined prehistoric productions, both for the quality of the ceramic mixture and for the type of decoration, belong to this ancient community.

In addition to cardium pottery, in the part of the cave that is currently below sea level, undecorated artefacts have been discovered. These can be dated back to the earliest phase of Sardinian Neolithic, which is recognised as Filiestru-Grotta Verde.

This name bears testament to the relevance of the site in reconstructing the early stages of Neolithic in Sardinia. Grotta Verde was in fact the site of one of the very first human settlements in the territory.

Shelter, dwelling, grave and place of worship: the cave has, even today, a lot to tell.

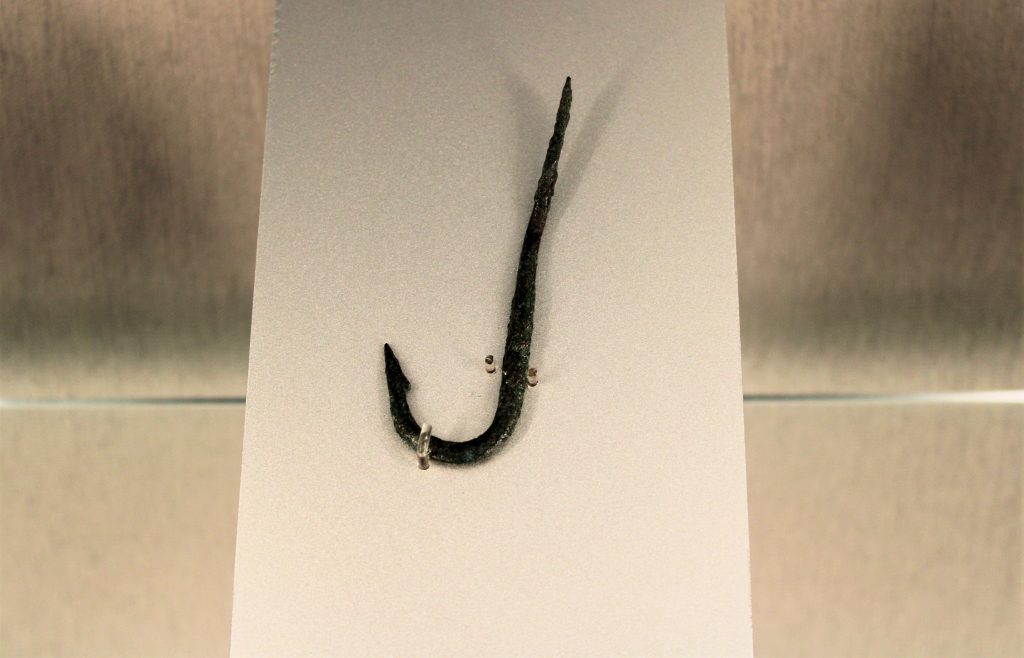

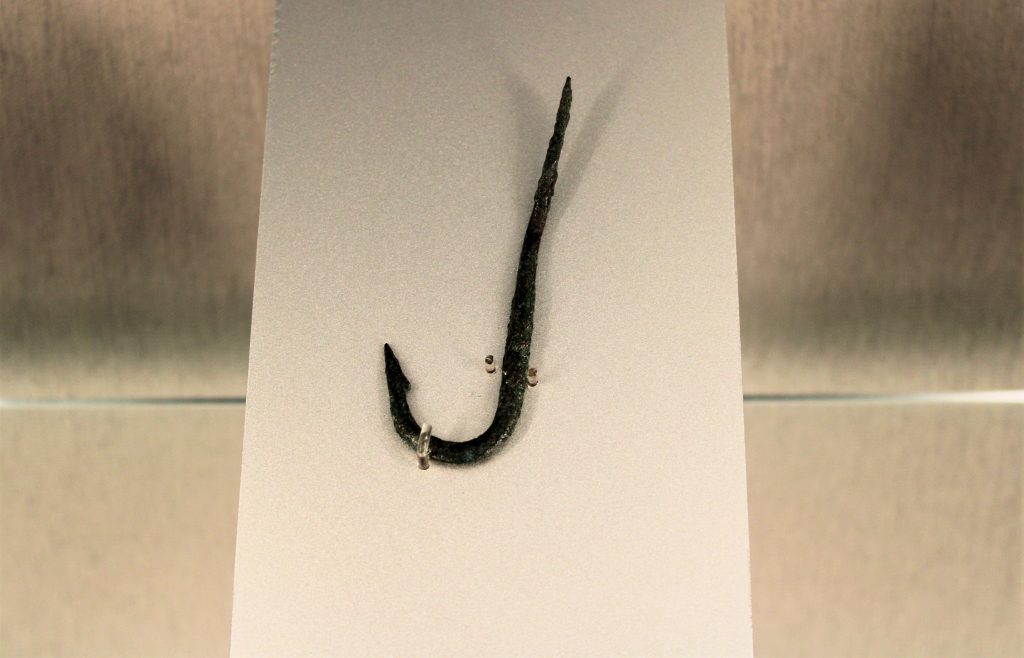

PALMAVERA NURAGIC VILLAGE

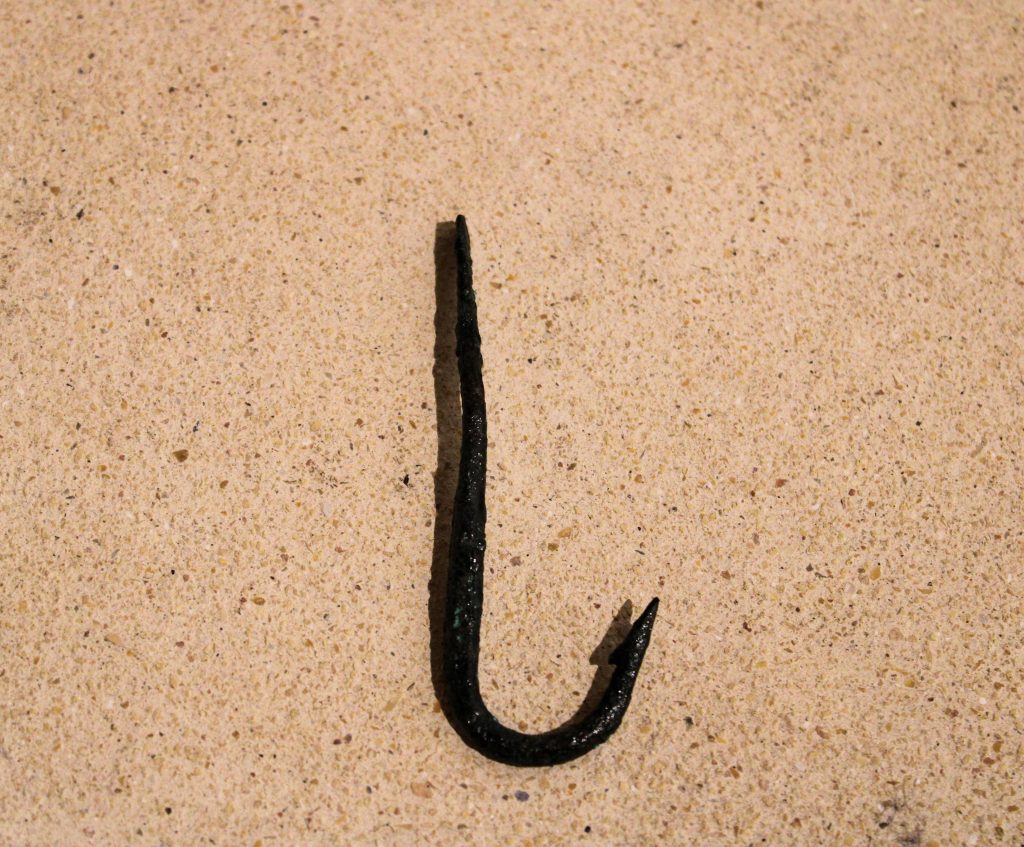

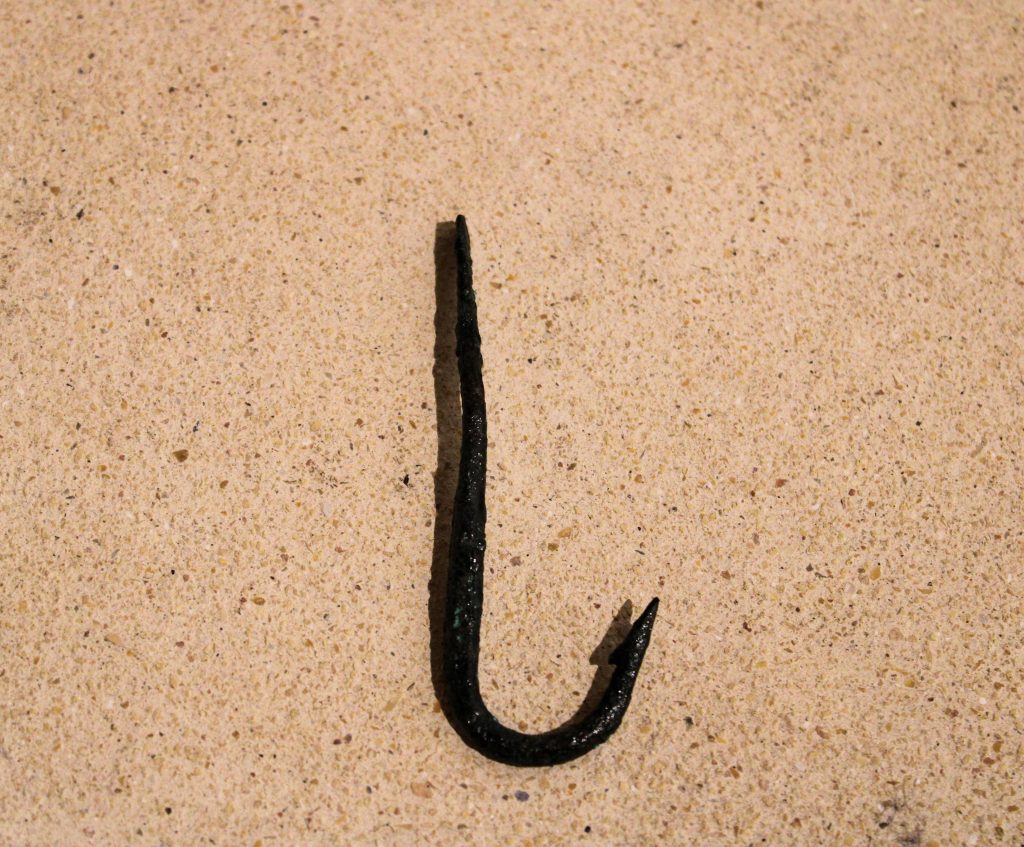

An unusual find in a nuragic context that captures our attention.

This fishing hook belongs to one of the most-frequently visited archaeological sites in Sardinia:

the Nuragic Village of Palmavera (Middle Bronze, XV-XIV century BC - end of VIII century BC

The settlement comprises several structural elements.

A complex nuraghe, it is the result of several construction phases.

A pentagonal shaped rampart (equipped with hut towers) encloses a large courtyard. The Capanna delle Riunioni (meeting hut) stands out for its size and features; this was a public place where the community could debate issues and celebrate rites and ceremonies.

Lastly, the vast village had numerous mostly circular huts that develop around the rampart wall.

Its position as a type of ‘lookout’ towards the coast and its close proximity to the Lazzaretto cove, just over 1 km away, lead us to understand that fishing must have been one of the town’s most important activities.

This small bronze object illustrates the importance the sea’s resources had for the economy of the village and suggests that this community had refined a fishing technique not so different from those used in later times.

The excavations also revealed abundant remains of molluscs, perhaps one of the villagers’ main foods.

It appears that women also contributed to fishing and to collecting seafood.

Unfortunately, this captivating scenario was abruptly ended following a violent fire at the end of the 8th century. B.C.

ROMAN VILLA OF SANT’IMBENIA

A splendid maritime Villa that stands out on the shore of the most sheltered point of the bay of Porto Conte.

This is how we can imagine the Roman Villa of Sant'Imbenia, thanks to the restoration of the materials from the excavations, their display in the museum and the reproduction of a room in the residence.

To date, and to our knowledge, the richest and most beautiful in Sardinia.

More than a single find, we wish to highlight a part of the reconstruction of the room inside the museum: the realistic reproduction of the polychrome marble slab floor.

The restoration of the opus sectile floor of Sant'Imbenia transformed an immense, laborious puzzle of marble and stone into a refined testimony of an environment of the opulent Roman dwelling.

The resulting reconstruction constitutes, in its hypothetical size, a unique complex of its kind in Italy, above all because it restores historical significance to the artefacts and enables us to envisage the architectural and decorative features of the villa and the lifestyle of the time.

In the context of Roman residential construction, opus sectile generally adorned the floors of rooms intended for the reception of guests, the so-called state rooms or reception rooms.

Here the owner held meetings, entered into political relations and concluded business deals.

As such, these were spaces intended for official use within the domestic walls.

The rooms were carefully decorated to show off the prestige and social status of the owner, his political influence and wealth.

The value, rarity and quantity of materials used to make this floor is seen in the variety of very expensive imported marble, coming from distant places of the Empire, such as Greece, Egypt and Asia Minor. This feature gives the Villa an "international" character.

It is easy to picture this precious floor in a rich, complex and high-quality environment, equipped with all comforts: spa area, cistern for water supply, sea view. In short, a luxury home that most certainly belonged to a high-ranking family.

We can imagine a sumptuous lifestyle befitting their high social status in which abundant food, good wine and cultural pastimes punctuated the long summer days.

HISTORIC CENTRE

The urban excavations in the medieval town of Alghero have revealed relevant information on the evolution of the city since its birth, on its trade and on the eating habits of its inhabitants.

The findings uncovered tell us a lot about the anthropological processes related to the daily life of the time.

In particular, ceramics is one of the most commonly-used indicators to trace the history of ancient trade and its influence on the habits, nutrition and culture of a people, being the most common artefact in archaeological excavations and the most resistant to chemical-physical agents in the soil.

The ceramics exhibited in this museum room arrived by sea mostly from Spain between the 14th and 19th centuries.

A large part of the artefacts of Iberian production uncovered in the excavations come from Barcelona, Tarragona, Valencia and Paterna.

From the second half of the fourteenth century, after the Catalans had repopulated the city and for the following two centuries, Spanish ceramics circulated in Alghero with absolute predominance over those of other origins (Tuscany, Liguria, Sicily, France).

Among these objects are commonly used glazed products, simple ceramics such as kitchen dishes, as well as higher quality majolica ceramics with refined decorations in blue or in golden or copper-coloured paints.

The first type include the characteristic green poal from Barcelona (the obra verda de Barchinona) jugs used to draw water from the well and fire pots (casolas).

Of the second type, we should mention the enamelled plate depicting Iberian fish and the enamelled majolica bowl decorated with crowns and made in the Valencia area.

The extensive marketing of Spanish ceramic products in Alghero makes us think of the city as being considered almost as a Catalan "internal market".

The regular commercial exchanges with the motherland and the high volume of goods undoubtedly stem from a strong demand for Catalan products due to cultural factors, such as food and culinary traditions, and to the deep anthropological link with the culture of origin.

These imports prompt the development of Sardinian production and highlight the evident morphological and cultural dependence that local craftsmen had to withstand from the Catalan models.

This situation also affected other centres in Sardinia, such as Oristano, whose production forms refer largely to Iberian prototypes.

ARCHAEOLOGICAL EXCAVATION IN THE JEWISH QUARTER (OLD CIVIC HOSPITAL. WELL IN THE JEWISH QUARTER)

In the Catalan language of Alghero, baldúfola is the name given to the spinning top.

In the past, the wooden spinning top was one of the most-loved children’s toys. On the streets of Alghero, youngsters had hours of fun making this wooden toy twirl for as long as possible.

These two spinning tops were found in the well of the medieval Jewish quarter and are believed to date back to the period spanning from the end of the 15th to the first decades of the 16th century.

The urban archeology excavation, carried out within the ancient Jewish quarter, unearthed objects that give us an insight into the habits which were common to the whole population.

In 1492, the Catholic King Fernando and Queen Isabel issued the edict expelling Jews from the Kingdom of Aragon. Until then, Alghero was home to the second most important Jewish community in Sardinia, the first being in Cagliari.

After the decree many families left the town and others converted to Catholicism.

The architecture of the Jewish Quarter reflects the status of its inhabitants: lavish palaces, courtyards, multi-storey houses, workshops and warehouses. The houses spread out around the synagogue, which was most likely located where the current Piazza Santa Croce is situated today.

The sacred realm

DOMUS DE JANAS OF TAULERA

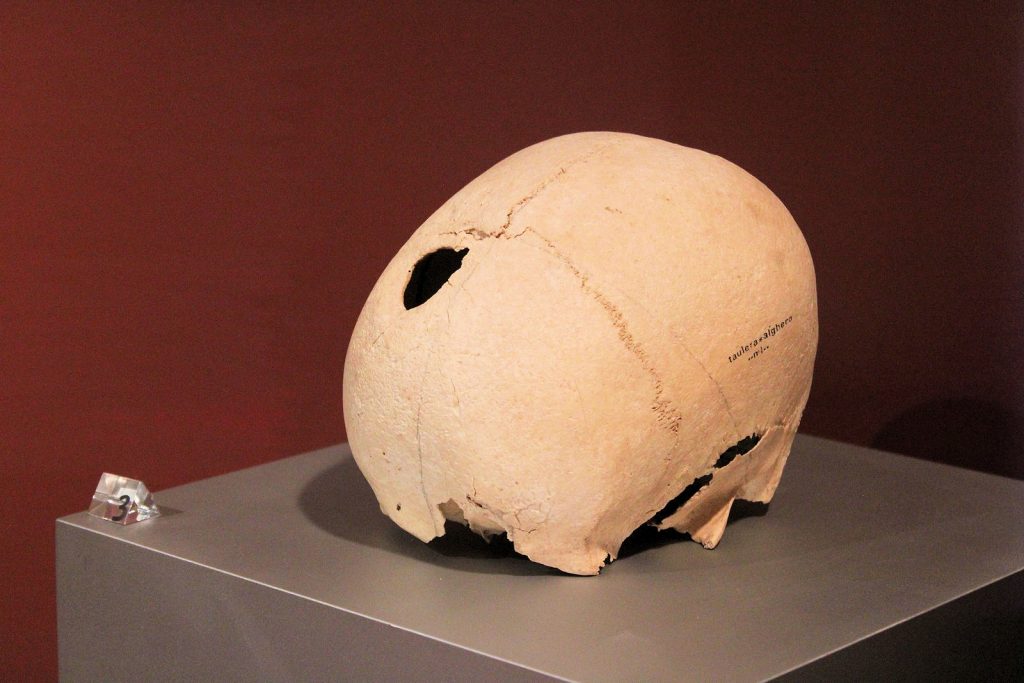

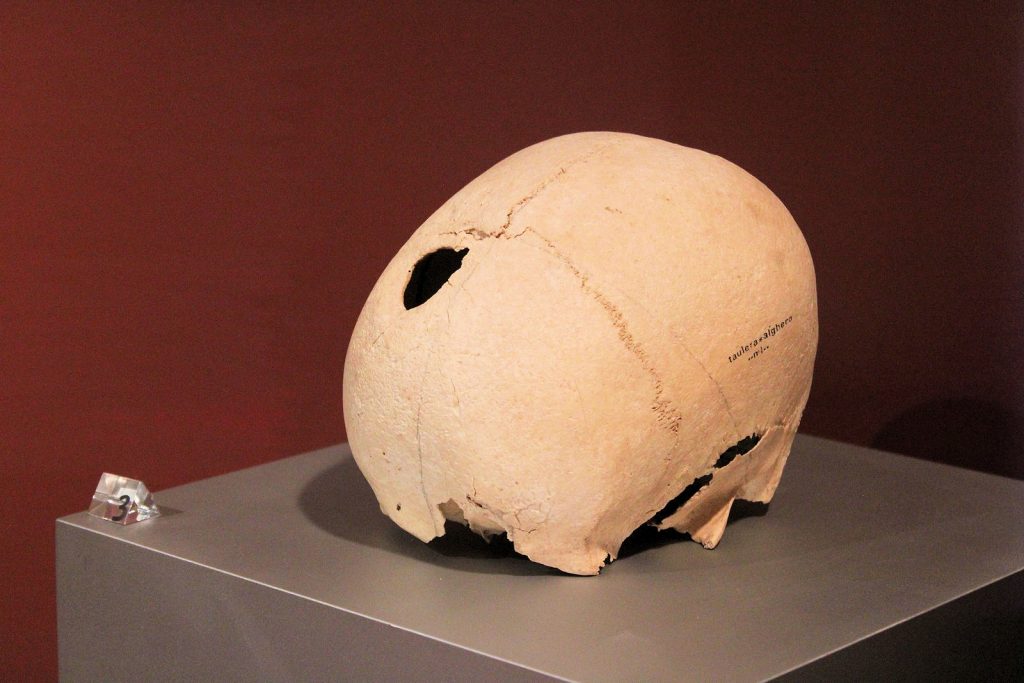

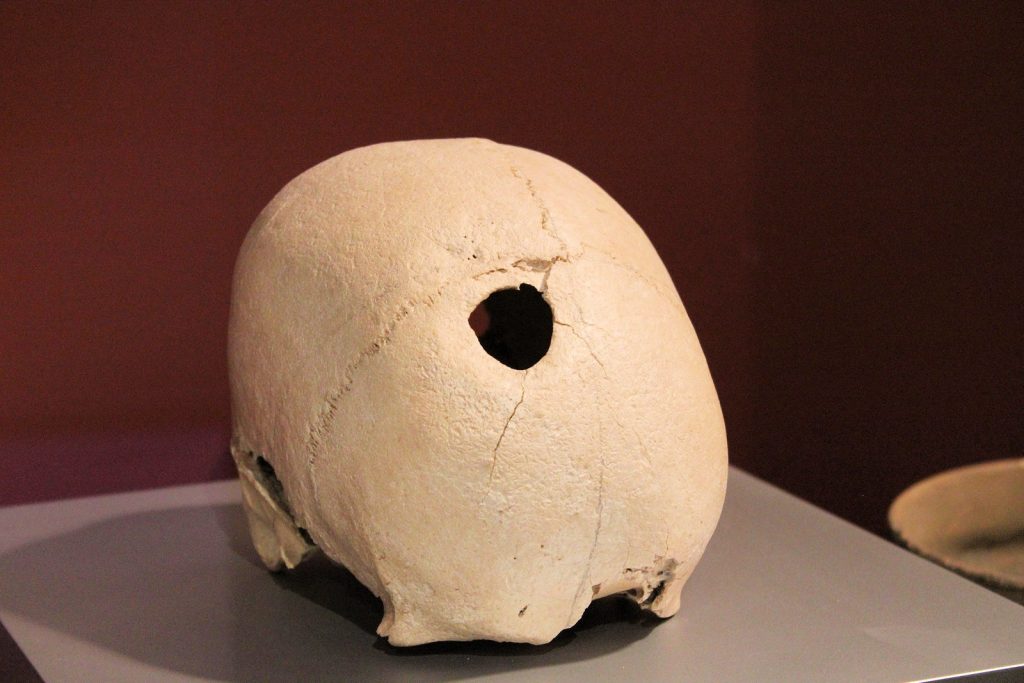

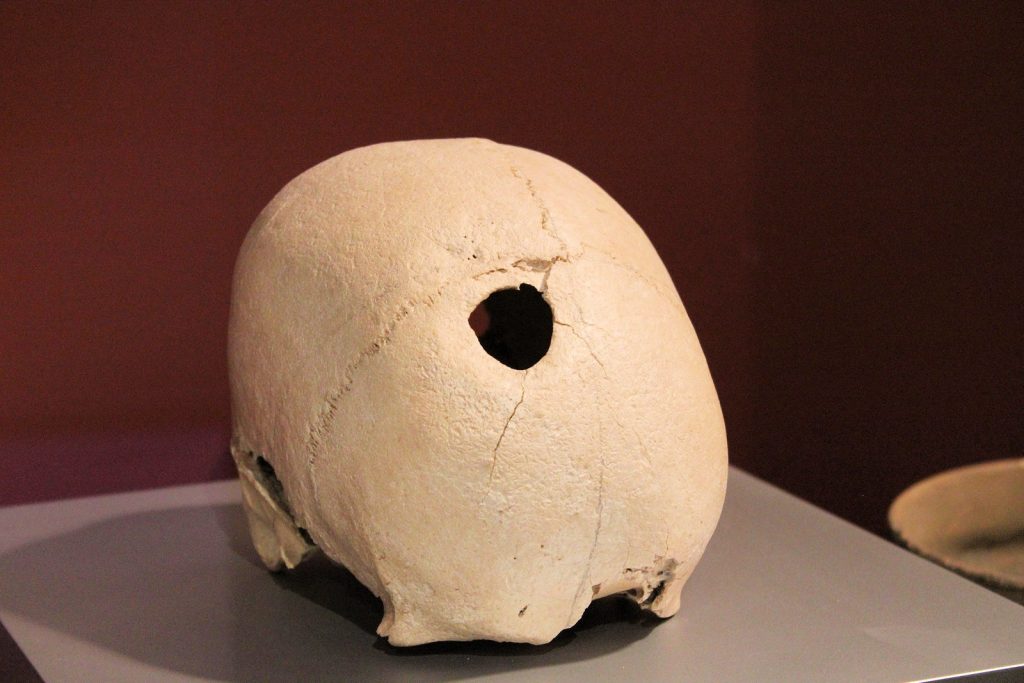

The skull exhibited in the museum belonged to an individual who lived about 4,000 years ago.

Its surface shows that it was drilled in vivo in two places. Between the first and the second operation the man survived for about a year: as evidenced by the scars in the posterior zone of the cranial bone.

Cranial trepanation was a widespread practice throughout the ancient world from the Eneolithic period (4,000-3,300 BC) until the Age of Bronze (2,300–1,700 BC), and represents the first form of neurosurgery performed by man.

It is assumed that similar operations had ritual and therapeutic purposes for treating pathologies and trauma. In fact, it was common for the “patients” to survive for a fairly long time after trepanation.

This demonstrates an in-depth knowledge, by the ancient peoples, of the anatomy of the head and of the technical abilities required to perform the operation while limiting risks. Furthermore, it cannot be excluded that these operations required the use of anaesthetics and sedatives, such as alcohol or drugs.

The archaeological find dates back to the Ancient Bronze Age (1,800 – 1,600 BC) known in Sardinia as the period of the Culture of Bonnanaro.

The only evidence of domus de janas present in the inhabited centre was found in the Necropolis of Taulera. The hypogeum was dug during the Recent Neolithic which, in Sardinian prehistory, is identified with the Culture of Ozieri (from 3,200 to 2,800 BC).

The domus has also been reused in the modern era, during the second World War, as an ammunition depot.

The activities during the war and the reuse of materials for urban construction, have damaged the Necropolis that has recently been retrained.

MONTE CARRU ROMAN CEMETERY

Between the 1st and 3rd centuries AD the area between the sanctuary of La Purissima and the Necropolis of Monte Carru, currently located north of Alghero in the Carrabuffas area, coincided with the ancient rural community of Carbia. The Roman settlement is present on the map of the main routes of the imperial provinces, the Antonine Itinerary.

It was in Carbia that, during the second century AD, the one who is today affectionately known as the Scolaretto di Alghero (the Schoolchild of Alghero) lived: a boy or girl who died between eight and ten years of age and was buried with the practice of cremation.

His (or her) grave, among the approximately 350 burials dug in the Necropolis of Monte Carru, held rare and precious grave goods that enabled a reconstruction the child’s identity and the important role that he or she held within the community.

The name chosen by archaeologists to identify the child already gives a good indication of the main task undertaken in life.

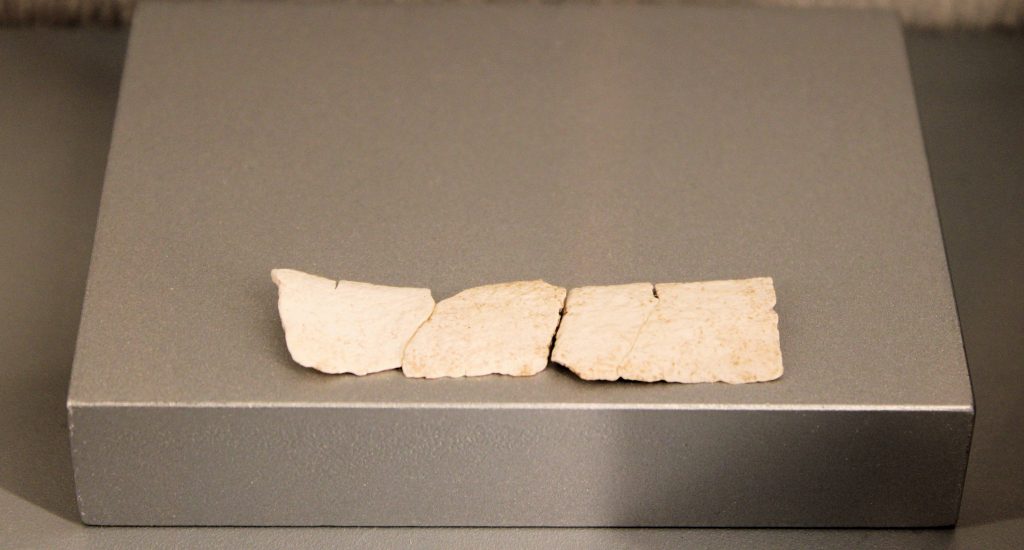

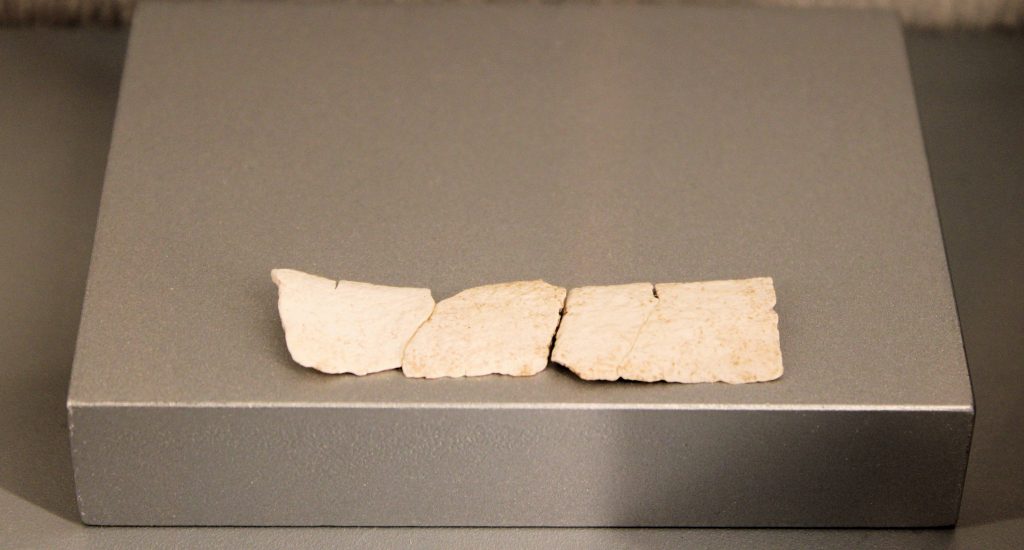

The finds really tell the schoolchild’s story: the remains of his/her body were in fact accompanied into the afterlife by a scribe’s writing set, composed of an iron spatula used to spread the wax on which to then engrave the words; a fragment of the frame of the bone tablet on which the child wrote; part of a bronze inkwell and a regolo mensorio (ruler).

The set’s extraordinary value consists both in the value of the individual objects in the context of Roman Sardinia and Italy, and in the rarity of finding them together.

Their discovery reveals how important it was to know the art of writing even in a provincial and peripheral context. The schoolchild was destined to become a prestigious contact for Carbia and the family’s affection has enabled us to remember him/her as such, even almost 2,000 years after death.

THE CEMETERY OF SAN MICHELE

This massive iron collar was wrapped around the neck of a young woman who lived in Alghero during the 16th century.

Her skeleton was found in one of the long, narrow graves in the cemetery of San Michele in the old town centre. These graves are burial trenches dating back to the 16th century, in which people were buried collectively.

The cemetery represents a discovery which is unique of its kind in Europe, both for its size and for the care and the attention with which the bodies were placed.

The site is defined as the town’s ‘biological archive’: the cemetery consists of individual and mass graves, was used for about 350 years between the late 13th century and the early 17th century, and houses the remains of our Ligurian, Sardinian and Catalan ancestors.

In the mass graves, specifically, entire family units in which the adults embraced their children have been found. The trenches are witnesses of the terrible plague epidemic which struck the city of Alghero between 1582 and 1583.

It is believed that this girl, too, died due of the infectious disease. What results unusual, however, is the heavy iron collar with which she was buried.

It would seem to be an instrument of thaumaturgic origin, which was used to “treat” people suffering from particular mental pathologies. The healing from psychic illnesses was attributed to Saint Vicinio whose symbol is the iron collar closed by two hooks, to which a stone is tied to weigh down the neck. This practice was forced on people who were deemed to be ‘possessed by demons’, during the exorcism.

There exists no evidence of similar finds in this territory. The young woman’s iron collar, thus remains shrouded in mystery to this day.